Today is Mother’s Day in the United States and just like many of you, I’ve spent my morning calling and texting the mothers in my life. I’m thankful I still share a home with my own mother and am able to hug her in the age of social distancing. Parenting- always an adventure as I’ve learned from observation- is even more of a challenge in the current times. Routines and norms are turned upside down, anxieties are more potent, and your children are, as one friend put it, “literally up your butt” 24/7.

Most of all, as a parent, you’d like to be able to tell your children it’s going to be okay. Right now, that’s more difficult than other times. It may seem disjointed to address the new development in the coronavirus pandemic making headlines this week, but on the day we celebrate the sacrifice and love of mothers for their children, it’s more imperative than ever to give you the tools you need to care for the little ones in your life.

The news this week has announced cases of what the medical community is calling Pediatric Multi-System Inflammatory Syndrome (abbreviated PMIS from here on) due to exposure to the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, the name of the virus causing the disease known as COVID-19. It has been compared to a similar inflammatory syndrome occurring in children called Kawasaki Disease or a condition called toxic shock-like syndrome. Since PMIS is a relatively new description of these signs and symptoms, let’s start by examining the known conditions it has been compared to.

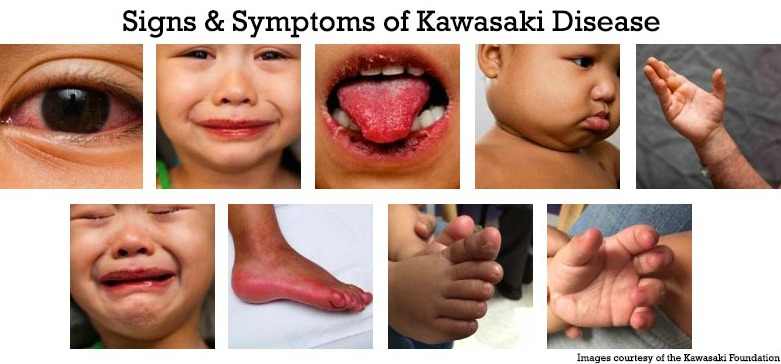

Kawasaki Disease

Kawasaki Disease- also known as Kawasaki syndrome or mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome- is an acute (short duration), febrile (fever-causing) illness that primarily affects children younger than five years old. It’s causes are unknown, though it is thought to be due to the body’s immune system reacting to a virus, bacteria, or environmental factor. It is not contagious on its own; you would have to be previously exposed to a virus or bacteria in order to develop this syndrome.

Kawasaki Disease results in the inflammation (swelling) in the walls of medium-sized blood vessels throughout the body (such as the coronary arteries supplying blood to the heart muscle). It is also referred to as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome because it affects the glands that swell and react to infections (lymph nodes), the skin (cutaneous), and the mucous membranes (like the inside of the mouth, nose, and digestive tract).

When a child develops Kawasaki Disease, they typically have signs (physical things you can notice) and symptoms (things the patient feels) in three phases.

- Phase 1 is identified by a:

- high fever (often higher than 102.2ºF/38ºC that persists for 2-3 days;

- extremely red eyes (conjunctival injection);

- a rash throughout the body that’s hard to describe with a single word (or polymorphus);

- red, dry, cracked lips with a red, swollen tongue (called a strawberry tongue or oral mucositis)

- swollen, red skin on palms and soles

- swollen lymph nodes, especially in the neck

- Phase 2 can be defined by:

- peeling of skin on the hands and feet, often in large sheets of skin (called desquamation)

- joint pain

- stomach symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain

- Phase 3 is when these signs and symptoms begin to end. Patients are often extremely fatigued and it may be eight weeks before energy levels seem normal again

While Kawasaki Disease is treatable if caught early, the main concern is its effect on the coronary arteries supplying blood to the heart. Inflammation can cause those arteries to change their shape, or remodel, leading to aneurysms (ballooned, weak arteries) and thrombosis (blood clots). Kawasaki Disease is one of the very few cases where children can be treated with aspirin; it’s anti-inflammatory effects that promote heart health in adults is beneficial to prevent remodeling of the coronary arteries. Of course, please DO NOT give your child aspirin; this is only safe under the watchful care of a medical professional. Aspirin in children carries its own risk.

Toxic shock-like syndrome

Toxic shock-like syndrome is typically caused by a bacteria called Streptococcus pyogenes or Group A Strep. Group A Strep is the most common strep-throat causing bacteria in children; it is also responsible for rheumatic fever. Streptococcus pyogenes produces a toxin called Endotoxin A that causes the body’s immune system to run into overdrive. Part of how the body deals with pathogens, such as bacteria and viruses, is inflammation; by making it uncomfortable for these pathogens to survive, the immune system can fend them off.

As you’ve read above (and as anyone who lives with an auto-immune disorder can tell you), the immune system can be too good at what it does. When the immune system encounters Endotoxin A, its responses and signals overwhelm the body. Therefore, toxic shock-like syndrome, in many ways, appears similar to Kawasaki Disease because it’s an overdrive of inflammation. Patients will present with high, persistent fever, rashes, and symptoms of shock such as cool, clammy, pale skin, rapid breathing, rapid pulse. Shock is when the body’s tissues and organs are not getting enough perfusion, or blood flow; no blood flow means no oxygen to keep those tissues alive and functioning.

So why is it toxic shock-like and not just plain toxic shock? Really, it’s just down to semantics and nomenclature. “Plain” toxic shock syndrome is defined as shock due to the toxic shock syndrome toxin (TSST-1) produced by a different bacteria Staphylococcus aureus. (People with uteruses who may have used tampons for their menstrual cycles may recognize this condition from the warning labels on those boxes, but that is another topic for another day.) Therefore, toxic shock-like syndrome is shock (with all the same symptoms and signs) due to the Endotoxin A of Streptococcus pyogenes. We would treat these in the same way: supportive measures to help your body get oxygen and blood to keep your tissues alive and antibiotics to cover all different kinds of bacteria (broad spectrum) before narrowing it down to a single antibiotic best suited for your case. See? Semantics.

So what do you need to know about Pediatric Multi-System Inflammatory Syndrome (PMIS) that is potentially related to the coronavirus?

While we have some theories, we don’t have enough information about why this is happening to children or exactly how long after exposure to the coronavirus that this can develop. One reason could be that children are developing this syndrome 4-6 weeks after exposure, even if previously asymptomatic, because their not-yet-fully-mature immune systems can be pushed into overdrive by this virus.

Basically, know how to recognize signs of PMIS necessary to seek medical attention! If the child in your life has:

- a fever of greater than 102ºF/38ºC for more than 2-3 days

- a rash, especially spread throughout the body

- abdominal complaints, such as stomach pain, vomiting, or diarrhea; or if your child is an infant, they are very irritable

then give your healthcare provider a call. I promise you, we as a medical community are here to listen and talk you through any of your concerns. You, as your child’s parent/guardian/caretaker, know them best and likely know when they aren’t quite themselves. Call us, we’re here, it’s what we do.

How else can you keep your child safe and healthy during this time besides continuing to follow social distancing guidelines? GET YOUR VACCINES! We’re seeing a trend in how many children are now not getting their routine childhood vaccines for diseases like measles, mumps, rubella, pertussis (whooping cough), and polio due to concerns for coronavirus exposure. These diseases are far more common and can be more dangerous than this rare condition of PMIS. Your healthcare provider will still see you in the office, with safety precautions, to keep your vaccines on track. You’ll give your child’s incredible immune system the tools it needs to prevent these common illnesses once this pandemic has receded and our children begin to play with one another again. No child wants to emerge from social distancing to return to isolation for a disease we can prevent.

And one final remark, Mother’s Day is not necessarily a happy day for everyone. On a personal note, today marks what would have been my Nana’s 89th birthday. A fierce woman, with all the grace and grit of a North Carolinian farm girl, my family often wonders what she’d make of the world we’re living in at the moment. As a babe born into the Great Depression, a mere child of ten years old when the U.S. entered World War II, and mother to the rambunctious motley crew that is my father and his siblings, I suspect she would have taken it all in stride and loved us and all people fiercely through it.

So, for those of you who may have lost mothers or lost children, for those of you who may not have the greatest relationship with your mother or your children, for those of you who had to be your own mother or serve as mother to your siblings, and for those of you who long to be a mother, today we think of you too.

Parents/Guardians/Caretakers: For more guidance on children’s health, please see the American Academy of Pediatrics website at https://www.healthychildren.org/English/Pages/default.aspx or speak to your pediatrician/healthcare provider.